This is a two-part post. If you're a geek, keep reading to the end. If you just want an update about how things were recently, by all means stop after the first part.

Last Friday had looked so promising in the forecast: wind all day, with mid-20s in the afternoon! Sunny and warm! But it started badly enough, by giving me the finger - a blue finger:

I am still thinking I should sue Chinook for failing to put a warning label on their booms that reads "

Remove fingers before closing". Fortunately, it's been too windy to find a lawyer. There's no fun to be had in court rooms!

Briefly, here are the other things that happened:

- My GoPro broke. Dead. Kaputt.

- When the chop and crowds became unpleasant in front, I sailed to Lewis Bay on my Skate 110/Idol 5.6 combo, and loved the flat water I found. Came back to switch to slalom gear and drag Chris along. Had an absolutely crazy, overpowered, out-of-control ride through nasty chop to make it back to Egg Island - the wind had picked up to averages above 30. Chris promptly declared Lewis Bay as "absolutely unsailable" and sailed back, leaving me alone. Considering that I had barely made it there, I had doubts that I'd make it back, so I stayed. At least there were no crowds. But there was the security guard now posted at Egg Island that makes sure nobody but birds set foot there.

- My Android phone that I use to announce my speeds through GPSLogit got wet and broke. This was the first time I had not double-bagged it, and also the first time I did not close the waterproof bag properly. It's terminally dead. Drying did not revive it.

So, here's a pop quiz: what do I call a day of sailing like that? Think about it for a minute. I'll even post a picture to create some distance from the answer.

The answer is (of course): A great day of sailing!

In the morning, I had a few hours of freestyle on what I count as a small sail. I even made one or two wet Upwind 360s - the "Andy Brandt" variety, where you leave the sail forward when you carve, and backwind before loosing all speed. Still had to waterstart out of it, but getting closer.

In the afternoon, I was eventually joined at Egg Island by my lovely wife, who was nicely powered on 3.7. That made me feel a bit better about thinking that my 5.8 was a tad big, especially since the wind had dropped by then. I watched here hack away at the Flaka, with a few good tries. She now has tried Flakas on sails from 3.7 to 5.6 m .. impressive. I still think she'll get her first Flaka before the Cape Cod ABK camp in September.

I did not try anything, but practicing slalom sailing was fun, and I later got some perfectly flat spots for full-speed jibes - so cool! I ended the day with a final session on my 3S 96 with my Idol 5.0 in front, bumping and jumping. 125 kilometers of fun! Who would complain about a blue thumb and a couple of broken toys?

But I wanted to replace the GPSLogit phone, and picked up a Samsung Galaxy J1 for $30 at the local Best Buy. First order of business was checking how well it would work in comparison to the "standard" GPS units.

Warning: here begins the geeky part of the post. Continue reading at your own risk!

So I taped the phone and two Locosys GPS units to the dash board of our Nissan NV 2500 high roof van, and took the babies for a ride. The GPSLogit speech announcement worked as expected, and the speeds always agreed well with the speedometer. I even stopped in the middle to switch the GW-52 from 5 Hz recording to 1 Hz recording, just to see what happened.

Let's start by comparing the phone data with the GT-31 data. Here's a part of the doppler speed graph (click on the image for a large view):

|

| GT31 (blue) vs. Samsung Galaxy J1 with GPSLogit (red) |

The first impression was "pretty good", but a few small spikes are visible in the phone data. Here's an enlarged section:

The red phone data are a bit noisier, and have a few spikes that may overstate the speed by a knot or two. Indeed, the speed results in the GPS Team Challenge categories showed that the phone speeds were a bit higher than the GT-31 and GW-52 speeds (up to about 1/2 knot) - something that was seen before for other phones. But while the accuracy is not good enough for posting to the GPS Team Challenge, it's definitely good enough to hear how fast you are going while you're sailing. Great!

When I compared speed results from the GT-31 and the GW-52, the differences were minimal, as expected. However, there was a very noticeable difference in the 5 Hz data from the GW-52, compared the the 1 Hz data from the GT-31:

|

| 1 Hz GT-31 data (blue) compared to 5 Hz GW-52 data (red) |

The GW-52 were collected every 0.2 seconds, so we have five times as many data points as for the GT-31 data which were collected every full second. The GW-52 data have a lot more spikes - little ups and downs. That had been reported by others before for windsurfing data, and the question arose whether these spikes are real differences in speed, or noise that was caused by the higher measurement rates. We'll get back to that question in a minute, but let's look at a comparison when the GW-52 unit is set to 1 Hz:

|

| 1 Hz GPS data from GT-31 (blue) and GW-52 (red) |

The data look very similar.

So, let's have a closer look at the 5 Hz data. There are valid arguments that can be made why collecting data at a higher frequency is better. If (a) the errors in the speed measurement are purely random, and (b) the error per data point is the same at 1 Hz and at 5 Hz, then measuring at 5 Hz would give about 2.2-fold higher accuracy. But this is only true if both of these conditions are met.

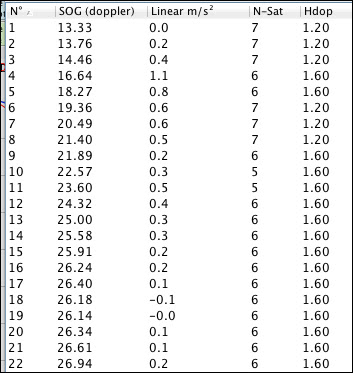

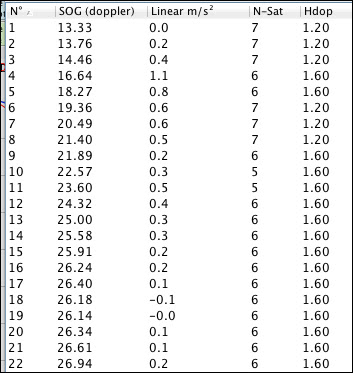

Let's look at the data points (I used GPS Action Replay's "Trackpoint Table" to create the screen shots):

|

| GW52 "raw" 5 Hz data from a small subregion |

For comparison, here at GT-31 data from the same region:

|

| GT-31 data (1 Hz) |

A picture says more than 100 words, so here is the doppler speed graph for this region:

|

| 1 Hz GT-31data (blue) and 5 Hz GW-52 data (red) |

When we seen spikes like in the red curve about in windsurf data, we may believe that they are real: we constantly hit chop, gusts, and lulls, and it seems quite possible that our speed changes several times within a second. But the data above are not from windsurfing, but from driving a big, heavy van. The Nissan NV2500 High Roof van is quite a beast. It weighs in at about 3 tons (6250 lb), and we've loaded it up with interior racks, 6 boards, 15 sails, masts, booms, etc. Does it change speeds several times a second like the GW-52 data indicate? Allow me to cite from The Princess Bride:

"Inconceivable!"

We can get a bit more formal in analyzing this. We can start by looking at the acceleration - the change in speed from data point to data point. The acceleration is shown in the tables above as "Linear m/s2". In the GT-31 data, the values change little from data point to data point; but in the GW-52 data, the acceleration jumps from 0.4 to 2.9 in 200 milliseconds! That's almost no acceleration to 1/3 g. I'm sorry, but I don't drive

that crazy!

The change in acceleration is actually a pretty good indicator of noise in the data. It's pretty easy to calculate, and if you're mathematically inclined, you can call it the second derivative (the acceleration being the first derivative of the speed). Here's a graph of the acceleration and noise for GW-52 data:

For comparison, here is what this looks like for the GT-31 data:

That's a lot less noise in the G-31 data! The 1 Hz data do reflect reality better: I accelerated somewhat evenly over about 15 seconds, kept the speed more or less constant for about 1/2 minute, and then slowed down constantly.

This is some rather clear evidence that collecting GPS data at higher frequencies does indeed introduce addition measurement error, which negates any potential advantages of the additional data points at least partially. More data is just that -

more data. It's not automatically better data. Nor does a lower error number that some software spits out necessarily mean that the data are indeed more accurate - if basic underlying assumptions are invalid, then the error numbers will also be invalid.

--

Some of my readers may wonder: "Who are you that you think you can analyze this, and go against what everyone else says?". Well, that is a valid question. I admit that windsurfing is my primary addiction, but I have some scientific background. I got a M.S. in Biophysical Chemistry, a Ph.D. in Experimental Sciences, and have worked in scientific data analysis and software development for Bioinformatics for last 3 decades. I certainly enjoy developing algorithms for large-scale (and small-scale) data analysis... especially when it's not windy.

I

I